Phallic graffiti

The plexiglass prism of the bus stop window captures the evening light, cascading through the gaps in the road grime, where idle fingers have doodled in the dust. I always pause to read these illuminated hieroglyphics, as they can often feel like a rare insight. It’s in these kinds of places you wouldn't be surprised to see the most common graffiti in the UK: The penis.

This rudimentary sigil of three lines (more for creative embellishments like pubic hair or ejaculate) is unspeakably common, yet somehow escapes our in-depth scrutiny. Even me, someone who implores empathy for all forms of graffiti and delights in street-marginalia, has never truly asked myself: Why do people do penis graffiti- why have I done penis graffiti?

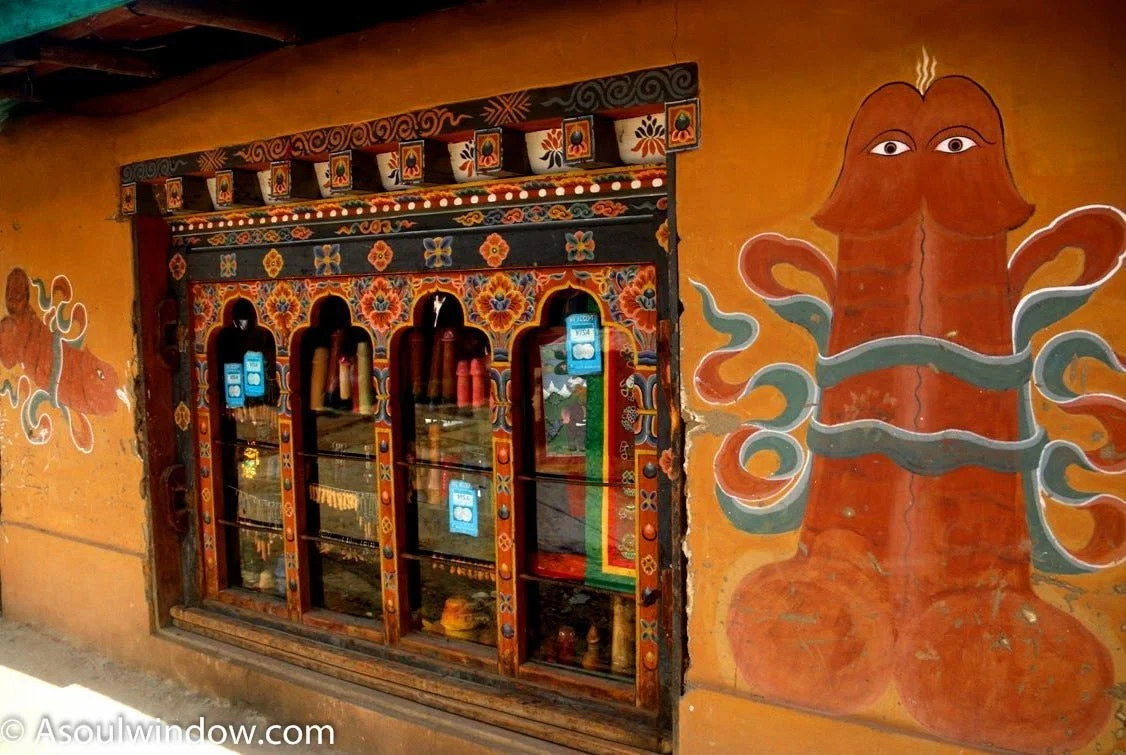

In me I find a rare confluence of both having drawn more than my fair share of penises and being capable and passionate about deciphering our long relationship with this symbol. As I delved beyond my initial concept of the crude, cartoonishly rendered penis as an anti-social icon, I realised my connections to it were numerous. Not least with the Buddhist saint who appeared to me during a meditation retreat in Thailand. He was known for slaying demons with his penis and inspired a culture of Bhutanese pro-social penis murals. Somehow a decade later, I have found myself back at home, in a veritable wonderland of ancient penis art. Some of the most important phallic-art discoveries have been right on my doorstep.

Bhutanese penis mural and Roman graffiti from Hadrian's Wall translating as 'Secundinus The Shitter'

Of course the internet yields riveting tangents on the search for reason among a nation of criminal penis artists. We are not lacking examples of or theories about phallic art: From Freudian castration fears to aggressive ‘sword-wielding’ dominance displays, my own thoughts took me back to my childhood and the incubator for phallic artists: School.

Violinist

As a child I was sent to a Church of England school, not because of my family being religious but for the presumed discipline. Primary school is the first time I remember being fully lucid whilst pointlessly interned. Looking back through my school books, there were countless pages where I had written the title and date, but the page would be blank. Occasionally the red pen of the teacher would be scrawled hastily on a diagonal, outside of the lines we were told to keep so closely inside of.

“WHERE IS THE WORK?”

“WHAT WERE YOU DOING?”

“SEE ME.”

It wasn’t long ago that I threw these books away. The idea that there was something wrong with me, not with how I was taught, still brought shame to mind when I looked at them. The only page I ripped out and kept was from Religious Education (RE) which seemed to summarise the effortless artistry that could have been nurtured a bit better.

My first homework for my new RE teacher, me, aged 11

Being taught about religion by people who are not spiritual themselves is enough to put someone off spirituality for a lifetime. I would have garnered more appreciation for God if I was left in a field and allowed to pick and dissect plants with my fingers, appreciating the membranes. Instead I spent most of my childhood feeling cool plastic desk on my forehead as the world’s most sacred texts were explained to me by someone whose bad breath would pervade the classroom, soured by an hourly deluge of instant coffee and sachet milk cocktail, their eyelids pulled open by the skin of their forehead, stretched back by hair tied aggressively tight behind their head.

I had slipped to the bottom of the class with my reading, until the excitement of Pokémon cards evolved my reading level way beyond the standards of my age. The signs seem obvious now I did not fit into the standard learning model, but with this unusual way of learning to read I have my earliest memory of success in school, I was able to read all the words in the test but one I had never seen before and could not pronounce: violinist.

It was only as I discovered graffiti at 13 that I remember school becoming okay for me. Something to do, to draw, to dream about. My entire time in school I had been told something was wrong with me. The success of the violinist was so rare and always arrived in the niche moments, beyond normal school work. Graffiti gave me the freedom from approval that I desperately needed.

Once I had delved uncontrollably into my passion, the approval I had been seeking of course came with it. Inspired by the on-ramp to hip-hop of House of Pain's ‘Jump Around’, I tagged the lyric ‘WORD 2 YA MOMS I CAME TO DROP BOMBS’ without a hint of sarcasm, on the outer walls of the toilet cubicle. I watched in delight as the wet letters gleamed, drips furrowing down the wall. The purple-black ink smelled like a deliciously putrid marzipan.

Images taken from several articles in the Northern Echo related to a graffiti spree and my subsequent arrest for criminal damage at 13. 'A gang of teenagers, all aged 13, from Newton Hall, was caught in the act by the police earlier this year. One group member was prosecuted. Police Community Support Officer Jean Fletcher said: "This problem has been going on for a while. It is affecting the whole of the estate. We are talking about nearly every lamppost, telephone box, street sign and dog bin.'

Brazen acts like this are made possible when graffiti on the walls becomes the new baseline. When someone can walk into the toilets and not notice the graffiti, it makes some people feel safe taking part, but it also makes people want to break out of that camouflage. I want to do graffiti that’s more stylish, bigger and uses more rap lyrics than anyone else. Graffiti writers are in this constant search for novel work that has visual hooks in the medium, the method and the meaning.

Having matured, I now tag the inside of the toilet cubicle door. The cleaner never locks themselves in to clean and when you sit down, you are forced to read my name. Tags here last longer and can be produced even in a busy bathroom. I also enjoy that you discover my tag like a wide eyed dog, vulnerably looking to its owner for protection in your most private moment.

Graffiti encourages you to see the world completely differently. If you want to be known and assert yourself as an artist, you have to reimagine where and what you can paint across a constantly shifting landscape. It is at the same time competitive and isolating as it is collaborative. It’s no surprise this appeals primarily to young men. The craze I had ignited swept the school and it wasn’t long before incidents like this caught the ire of the teachers and the caretaker. A few people were caught tagging and their punishment was haphazardly handed down to them.

‘Repaint the toilets’

My friend who I asked about this time told me about how, left unattended, they painted every possible surface, including the mirrors, light switches and the toilet including the bowl. Blue.

I’m fascinated with the separate world you enter when you participate in graffiti, from the alias based lettering created with intention to the instinctively produced penis by someone who finds themselves with but a medium and anonymity. For those mistreated by the system as children, even through acts of unintentional neglect owing to their neurodivergence, graffiti can give a secret knowing confidence. It allows us to prove our worth to ourselves, and create enough ballast against the pressures of a society that tells us we simply do not fit. It feels like sitting in class, knowing there is a giant cock on the roof above you, just as Google Maps is an emerging technology.

Taken from the article 'School prank is spotted from space' Graffiti on The Friarage at Yarm School discovered and removed in 2006.

Bhutan

In my last year of schooling at 17 I finally discovered my love for reading and writing. After a decade of having my self-esteem eroded at school I felt useless and ill-fitting. The library was a place I could self direct my learning, with the solitude and freedom to follow what I was passionate about, just like in my graffiti where I thrived. The first books I found myself interested in were self-help books, made for people twice as old and half as sad as I was. The only book from this time that contained any revelations was a tiny pocket-sized ‘principles of Buddhism’ which no doubt had information that I’d already heard in a classroom from someone who had to sneak their empty bottles into the neighbour’s glass recycling every fortnight because theirs was full.

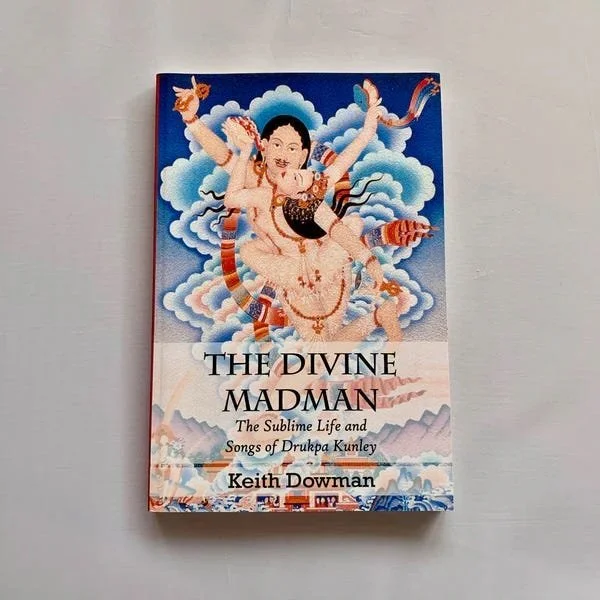

Instead of continuing on to university, I left to travel at 18, where my interest in Buddhism would take me to a meditation retreat in Thailand. It was here that I crossed paths with the ‘saint of 5000 women’ who was responsible for inspiring modern day penis murals in Bhutan.

On entering the monastery I handed over my belongings, donned white clothes and took a vow of silence for my stay there. My room was cell-like, with a simple bed and no other ornaments except a screen door which would occasionally be nosed through by friendly mountain dogs.

Deprived of stimulus one day I explored my room, discovering a single book under my mattress. Arriving as if divined, this unusual text is not something I would have chosen to have as my sole source of intrigue amongst the extreme sensations I was getting during meditation. I read the book in small stints during my stay, at once savouring and enjoying it, but feeling guilt for breaking the rules, which banned any forms of entertainment.

Drukpa Kunleigh was a Buddhist saint who was known for drinking, carousing and subduing demons with his penis which was dubbed the ‘Flaming thunderbolt of truth’. Modern day rituals that stem from Drukpa’s exploits seem harmless: inaugurating a new house by raising a basket of wooden willies to the roof, dipping a little wooden one in a guest’s drink, or simply bonking those seeking the blessings of fertility on the head with a silver member. It is hard not to see the stories through the lens of our Western ‘Gurus’ who use their apparent access to ‘spirituality’ to abuse others who seek it.

Our species has been artistically wielding the phallus from our very first forays into art. Changes in culture and policy have modified not just why we create it, but how we interpret and decipher those historical creations. I wish I could enjoy Bhutan’s murals for the blessings they are intended to be. I can’t help but feel that my initial hesitance to examine phallic graffiti and my inclination to produce it are symbolic of something very wrong with how we think about sexuality and gender roles in my country.

It feels impossible to separate our cartoon penis epidemic from the knowledge of the perpetrators being overwhelmingly male. In the context of my own culture these really do feel like masculine declarations. At their best: Cries for help from men whose own instincts are in conflict with the roles enforced on them by the patriarchy. At their worst: Endorsement complicity with the status quo and a willingness to defend it.

For answers to my questions, I would like to experimentally remove the illegality of these creations. In a society where graffiti was legal, we could understand how feelings of rebellion and otherness influence this art. We would be left with more balanced interactions between spaces and their users, not just the blank walls and advertisements that say: Do not Participate, keep out, we know you but you cannot know us.

Is it pure fantasy that such a place could exist? Legal graffiti?! Homoerotic camaraderie?! Swords?

Rome

In a cataclysmic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79AD, so much ash was ejaculated on the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum that it formed a protective layer, sealing a whole city in the midst of its daily life and all the minutiae with it. Much of the world's most absurd and beautiful penis art is found preserved there. From graffiti carvings to commissioned frescos in houses with themes spiritual, ludicrous and a mixture of both. It would seem graffiti and phallic imagery played an important role in Pompeii, with no laws to prohibit either. Graffiti flourished as a kind of social media, with declarations, arguments, poetry and political slogans all accepted as a consequence of walls being public facing.

“O walls, you have held up so much tedious graffiti that I am amazed that you have not already collapsed in ruin.” Graffiti from Pompeii

Broadly, the penis was seen as a potent symbol of protection and luck, its absurdity and humour forming part of that protection. Priapus, the oft-depicted demi-god who was endowed with a giant constantly erect penis, was also cursed with impotency and the inability to use it. His penis, as well as those painted on the walls and carved into cobbles, is always in some way a mockery. Laughter elicited from these depictions was a perfect antidote to the quite serious ‘evil eye’: a belief that many Mediterranean cultures held about curses that could come about from envious or malevolent gazes. The result of these could be anything from ill health, bad luck or lack of favour with the gods.

Phallic amulets were often given to the spiritually vulnerable or those likely to incur the envious gazes. In the House of the Vettii, a lavish villa in Pompeii, a mural depicts Priapus measuring his penis on a scale against a bag of money, with a basket of fruit in the foreground. The two freed slaves who made themselves incredibly wealthy merchants, no doubt had many jealous detractors because of their background. This mural adorning the front entrance to the brothers house seems to say something that chimes with our modern uses of phalli. Of the pride with which we display our engorged demi-god penis, even though it is ultimately grotesque.

Modern phallic graffiti feels like a declaration of freedom from the shame of vulgarity in order to establish power. A consequence of the self-shattering horrors of enslavement or church school and a desperation to assert oneself subsequently.

Priapus mural from House of the Vettii

Even within the context of their discovery, they were deemed vulgar by King Francis I of Naples in 1819, who was touring the site of Pompeii with his wife and children. Many of the lewd frescoes had already been concealed behind cabinets, opened only for visiting Gentlemen of high moral standing (for an additional fee). On the king's orders the censorship was formalised and much of the art was moved into a secret collection known as The Gabinetto Secreto, or secret cabinet. The devout Catholic king, in attempting to enforce his ideals of moral conservatism, somehow made the collection even more sexy. At one point the entrance to the collection was bricked up by Francis’s son Ferdinand in a display of pent-up sexual frustration. Ferdinand II was one of 12 children from a marriage between first cousins, Queen Maria Isabella being wed to Francis I when she was only 13.

Pan copulating with goat, at one time part of the Secret Cabinet

It was only after the fall of this dynasty of tyrannical inbred-paedo-patriarchs that the entrance to the secret cabinet was rediscovered in the unification of Italy in 1860, before being fully opened to the public in 2000 for the first time.

Imagine how much ‘lewd’ art has been hidden, misrepresented or destroyed by past and present prudes making up for their own urges. It’s no wonder these things are lurking in our subconscious, walled off. When we search for a subject in the exciting act of illegal graffiti, there we find the phallus.

Rome to Home

The fact that the Romans were forced to a halt in my region is a matter of pride. Erection of the 135 mile-long Hadrian’s Wall must have been incredible and fearsome for the border people. Marking the edge of ‘civilisation’, here was a clash of cultures so ultimate, it stopped one of the greatest empires in its tracks. The Roman symbol for luck, fertility and warding against evil takes on a different meaning when the thresholds are not doors to our homes, but castle walls and ramparts.

One item truly defines Northumberland as an important site for phallic artcheology. Not only is it the oldest disembodied life size wooden phallus ever found, but it was initially discovered and categorised in 1992 as a darning tool (for fixing socks). It’s interesting to imagine a team of archaeologists brushing the dirt off this very obviously phallic item and coming to an otherwise consensus. Far from the anonymous graffiti artists that are more than ready to create phalli where there are none, these archaeologists apparently pushed it from their minds.

These Romans may have ground their herbs with a penis pestle, touched a disembodied phallus before leaving their house for good luck, or brought a dildo to their deployment because they knew it would be boring. All of these potential uses identified in the 2023 re-assessment of the ‘darning tool’ clearly speak to the power that the phallus had as an icon. Outside of Rome, and the lavish Pompeian orgies, is the phallus still lucky, when that luck is conferred on a subjugating force in a barren and hostile land?

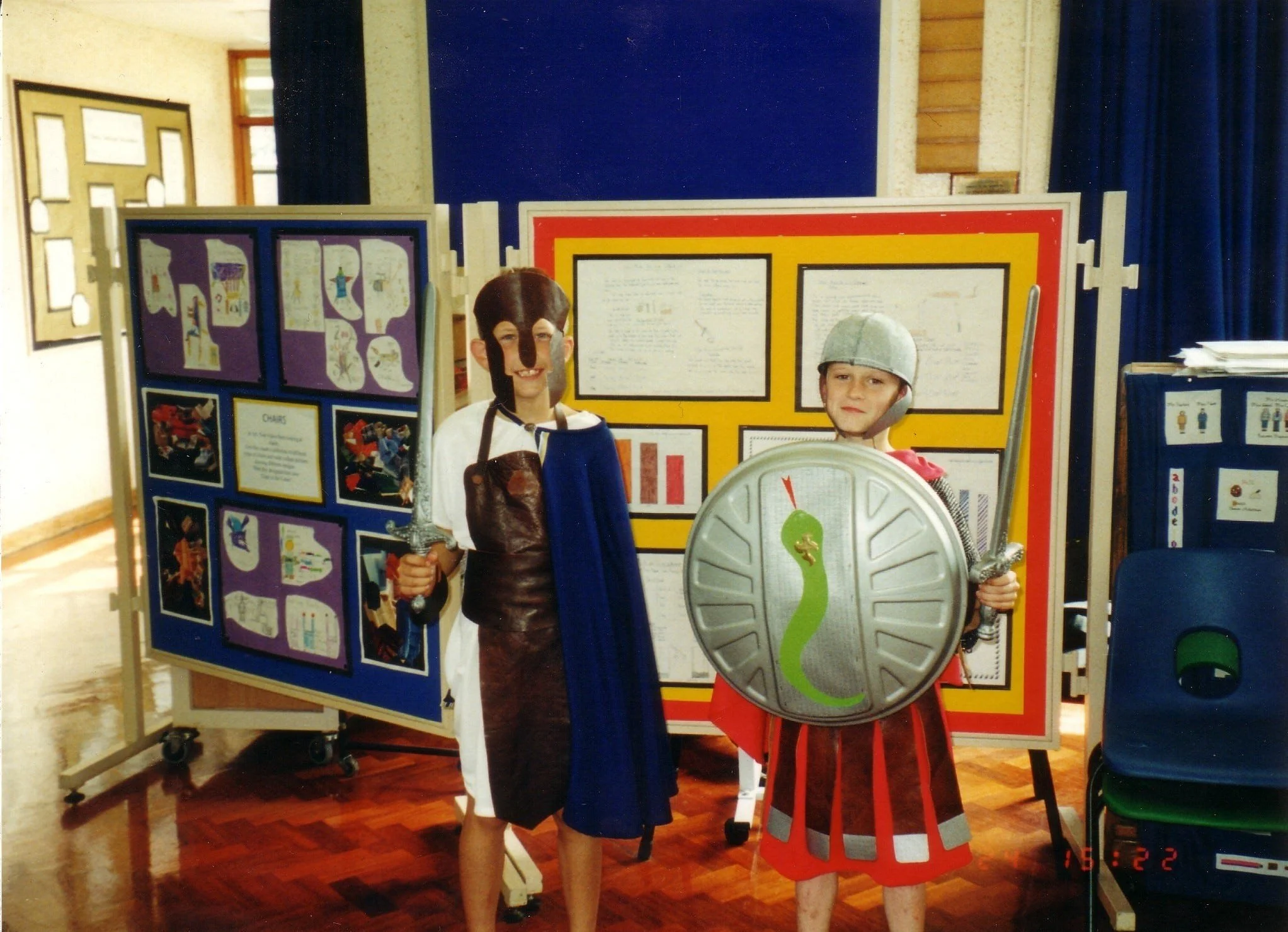

Me dressed as a Roman soldier in primary school

Along Hadrian’s Wall there are 54 recorded instances of phallic graffiti ranging from the endearing and spiritual to the fearsome and undermining. Here we see the Monosodium Glutamate of art, its magic enhancing whatever it accompanies, for better or worse. Are our disillusioned young men much different to those that were stationed along this wall? They embody the worst parts of fantasy Roman life, with it a corrupted and cruel use of a sacred symbol.

Anti-soc

Even though penis graffiti seems wholly rebellious, are these artists really just Roman soldiers standing atop Hadrian’s Wall naked from the waist down? Are they Bodhisattvas simply spreading enlightenment via intercourse? Graffiti is at least an outlier amongst other anti-social mediums with less artistic potential like spitting, public intoxication or playing loud music. For me, there is always more creation than destruction in graffiti, and for its perpetrators I am always called back to the phrase:

‘The child who is shunned by the village will burn it down to feel its warmth’

What else can we ask them to paint? These Romans away from Rome. Why do we blame the artists and not the schools they draw penises on or the communities where the only canvases for expression are mucky bus stops? Graffiti can say as much about the wall as it does the artist. Perhaps the penis artists sombrely wield their impotent erections like Priapus, idealising Ancient Rome as the definitive masculine society. It is no wonder they choose this powerful symbol in their search for meaning.

I arrive back to thinking of graffiti as something essential, an intuitive expression of self that is forced into the narrow field of illegality, affected and imbued with the ideas that our very urges to be known, to interact and to feel welcomed by our spaces are shameful and ‘illegal’. Illegality is what makes graffiti so special, yet I feel a sadness for those who draw penises on bus stops, thinking to themselves ‘this is what makes me different’ rather than ‘this is what makes us the same’. Graffiti can always be a reminder of our shared humanity, while it is illegal we must seek to understand those who pass that threshold, as they do not do so lightly.

Though I feel somewhat closer to understanding why we have such a connection to phallic graffiti, I’m more interested in my initial hesitance to interpret or question why it is so common. Its bold magical presence demands our attention, forcing us to confront something we would usually dismiss. Perhaps, for those who draw it, the act is not about the symbol but a desire to provoke, to make people stop and ask why, even if there truly is no common answer. The simplicity and boldness of the image make it impossible to ignore, and in that lies its power: a raw, unfiltered expression of a need to be acknowledged that forsakes decency and law. Seen this way, it stops being a meaningless doodle and becomes a plea for connection—a deliberate act asking us to wonder not just about the graffiti, but about the person who put it there.